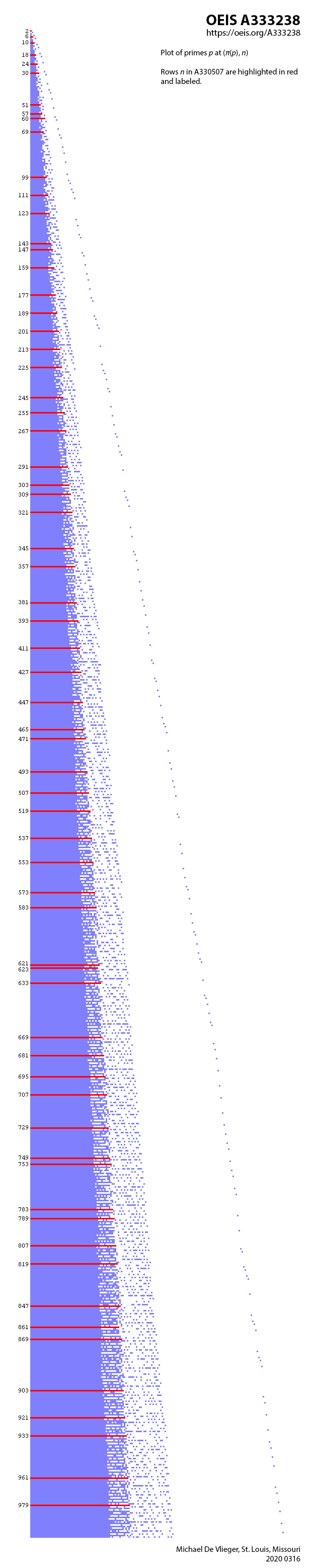

In Figure 1 twin primes are marked by light blue dots, and their associated tweens are dark blue.

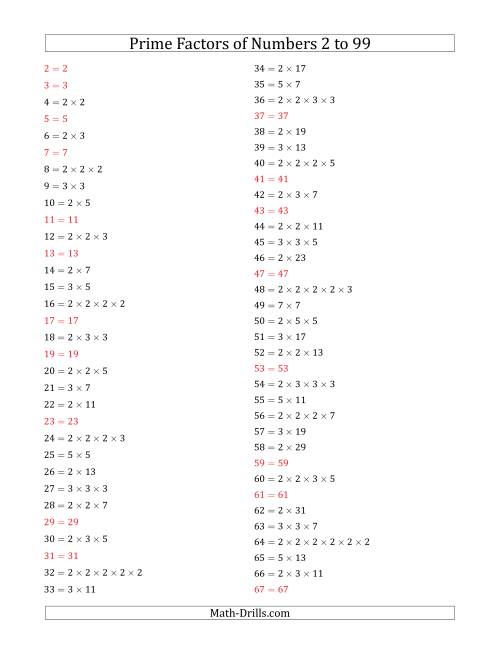

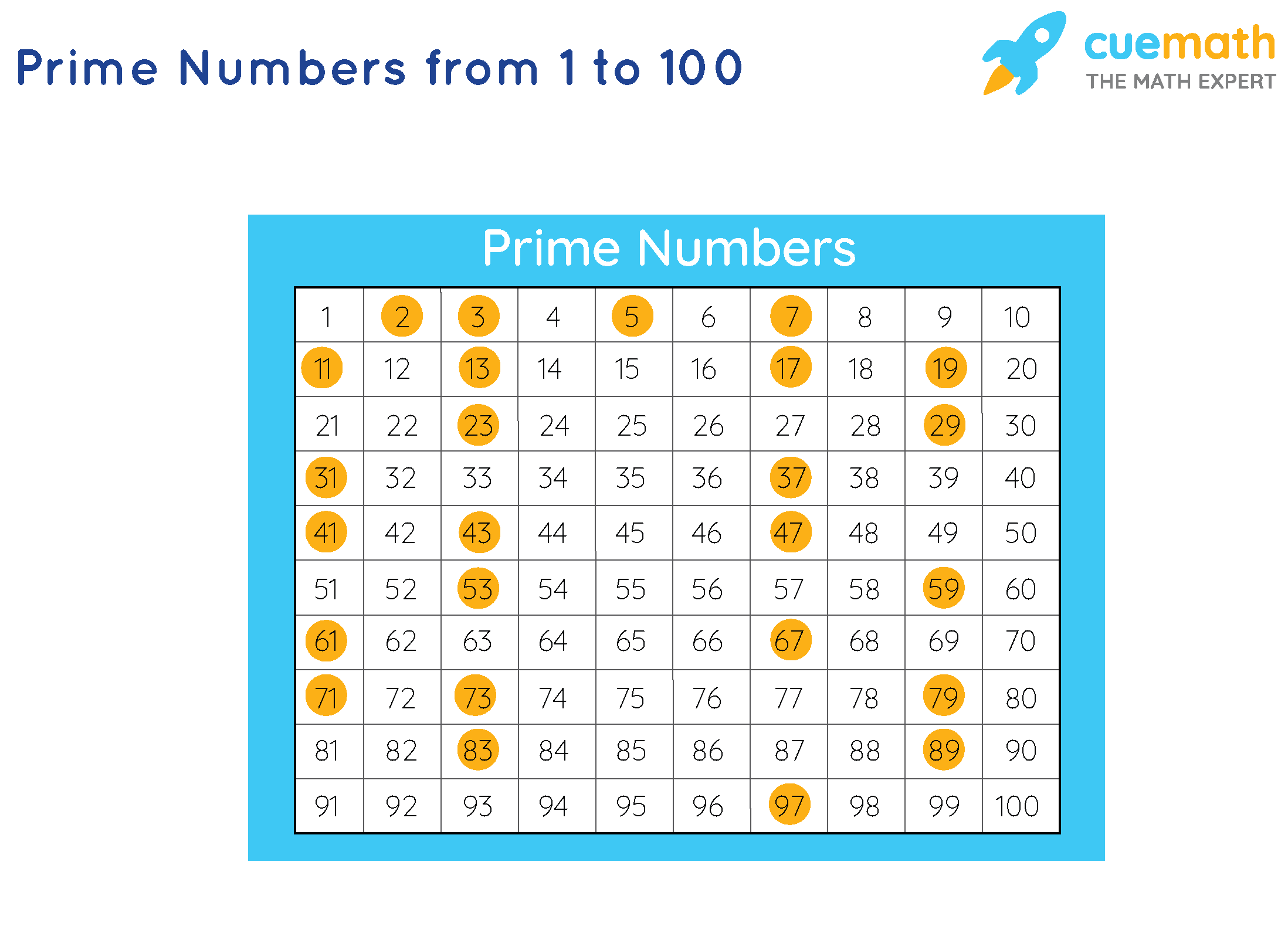

Perhaps every pair of twin primes forms a chicken salad sandwich, with two solid slabs of prime bread surrounding a squishy filling that gets chopped up into many small pieces.Īs a quick check on this hypothesis, let’s plot the number of divisors \(d(n)\) for each integer in the range from \(n = 1\) to \(n = 75\): Is it just a fluke that a number lying between two primes is outstandingly unprime? Is 60 unusual in this respect, or is there a pattern here, common to all twin primes and their twin tweens? One can imagine some sort of fairness principle at work: If \(n\) is flanked by divisor-poor neighbors, it must have lots of divisors to compensate, to balance things out. At the risk of sounding slightly twee, I’m going to call such middle numbers twin tweens, or more briefly just tweens. Less has been said about the number in the middle-the interloper that keeps the twins apart.

Over the years twin primes have gotten a great deal of attention from number theorists. Such pairs of primes, separated by a single intervening integer, are known as twin primes. The number 60, with its extravagant wealth of divisors, sits wedged between two other numbers that have no divisors at all except for 1 and themselves. There’s something else about 60 that I never noticed until a few weeks ago-although the Babylonians might well have known it, and Ramanujan surely did. No smaller number has as many divisors, a fact that puts 60 in an elite class of “highly composite numbers.” (The term and the definition were introduced by Srinivasan Ramanujan in 1915.) When you organize things in groups of 60, you can divide them into halves, thirds, fourths, fifths, sixths, tenths, twelfths, fifteenths, twentieths, thirtieths, and sixtieths. Lately I’ve been thinking about the number 60.īabylonian accountants and land surveyors did their arithmetic in base 60, presumably because sexagesimal numbers help with wrangling fractions.

This introductory page shows only the 2-dimensional regular convex figurate numbers ( polygonal numbers and centered polygonal numbers) and their associated 3-dimensional pyramidal layerings ( pyramidal numbers and centered pyramidal numbers, i.e. Figurate numbers, which are usually associated with the 2 or 3-dimensional figures, may be generalized to higher dimensions where they are often called polytope numbers and also to lower dimensions (where they are called gnomonic numbers and centered gnomonic numbers for 1-dimensional figures). For the Greeks of Antiquity, these numbers related either to 2-dimensional figures such as polygons, or to 3-dimensional figures such as pyramids. Since at least the time of the ancient Greeks, man has studied sequences of numbers which correspond to the geometric arrangement of like items (e.g.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)